Interpreting the lost village of Imber

Behind the wire and warning signs of the British Army training area on Salisbury Plain, lie the remains of a lost village. It is not alone; earthworks linger of eleven settlements vanished by the Middle Ages.

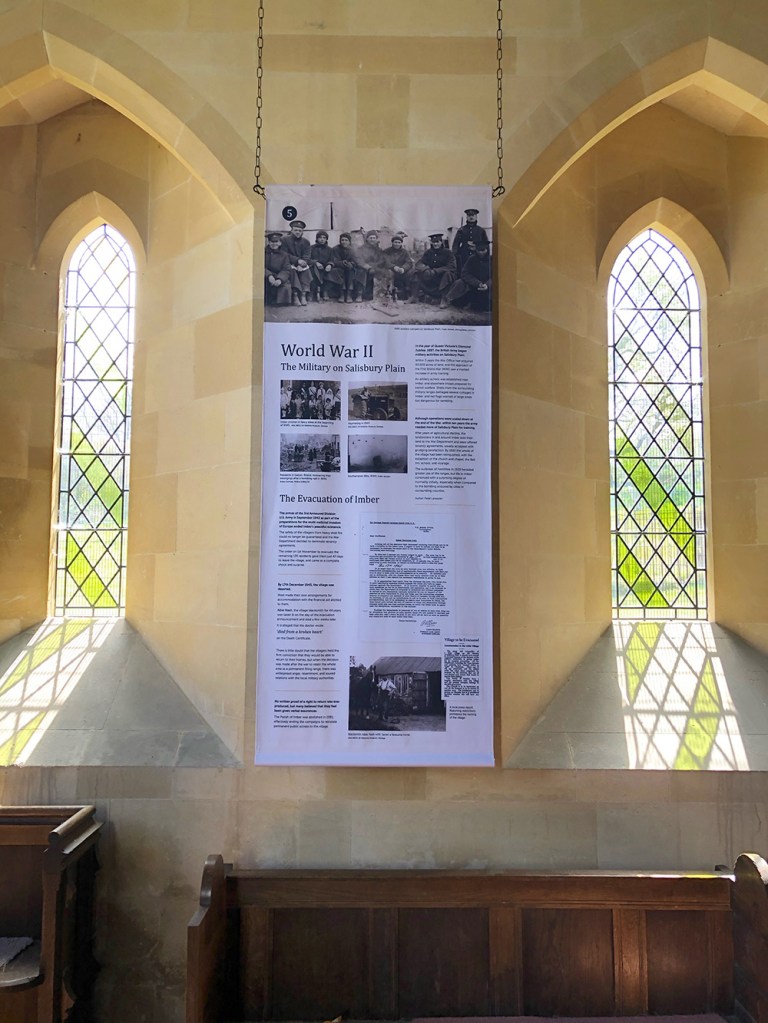

But Imber thrived in the medieval wool trade, survived centuries of thinly profitable sheep farming, and abruptly ended on 17th December 1943, when the village was evacuated during World War II. As the Allies prepared for the multi-national invasion of Europe, the MOD needed Imber for heavy armoured manoeuvres. Given forty-seven days to leave, the villagers thought to return but never regained their homes.

The evacuation of Imber is locally well-known, and told at the village church on the few open days permitted. When the rich collection of photographs and research by the Friends of St. Giles’ Church needed redisplaying, the task of interpretation became mine.

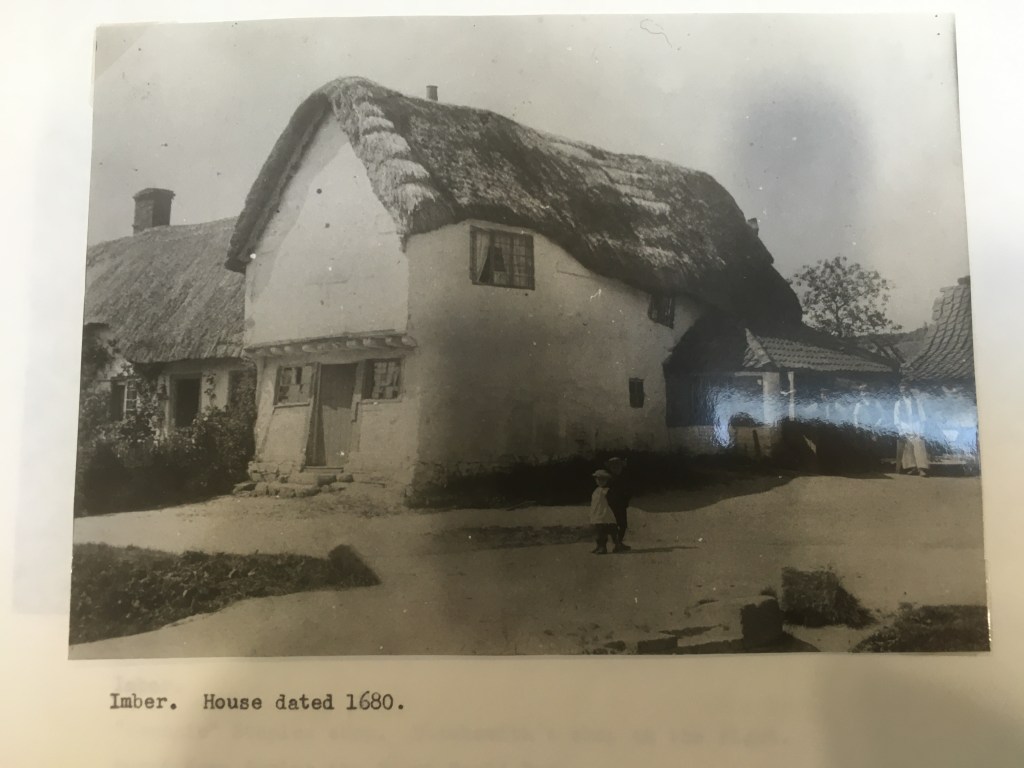

People feel deeply about the loss of the village, and the houses that no longer stand, but know less about the era when the church was built from 1280 to 1500, or about Imber’s rare living conservation today. I visited on a cold March noon, by special permission, when activity across the firing ranges was low. Driving over rutted tracks with Peter Lankester of the Friends group, it was hard to imagine the route had led to homes in the twentieth century; but for most of Imber’s existence it was like this, the road across the plain identified by chalk boulders in the turf.

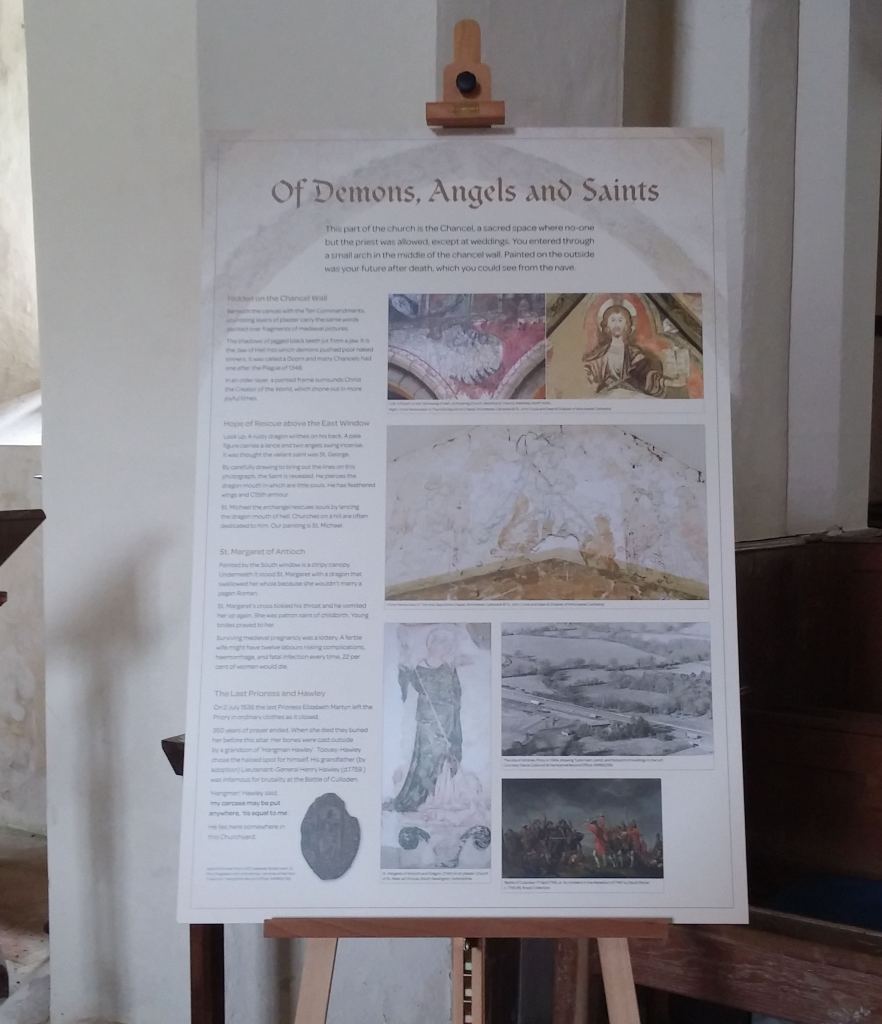

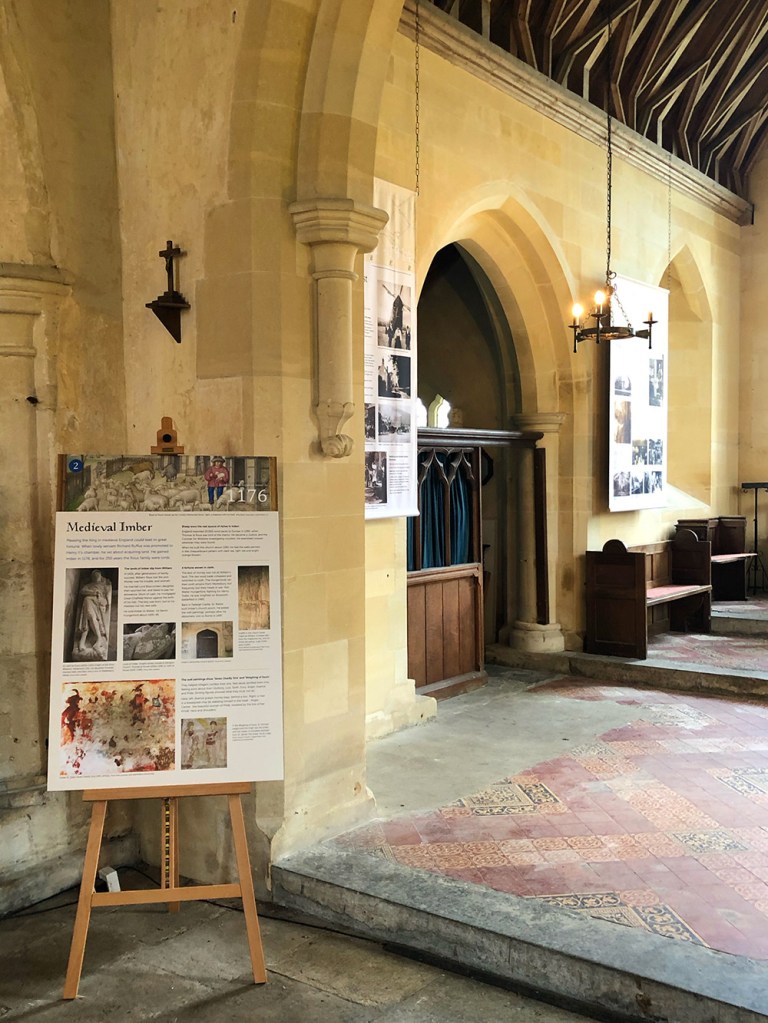

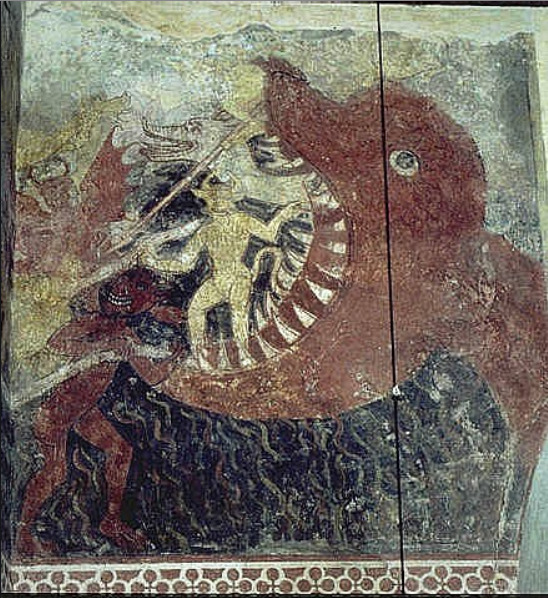

The church of St. Giles is one of a handful of buildings still remaining, cared for by the CCT and the Friends. Outside, the wild waste extends from the hillside graveyard, inside, the medieval past was flowery. The nave arcades were painted in C13th with a chequerboard of flowers, once dark and bright red, and brilliant orange. It was built by Thomas le Rous, lord of the manor, a Coroner for Wiltshire investigating murders were they lay.

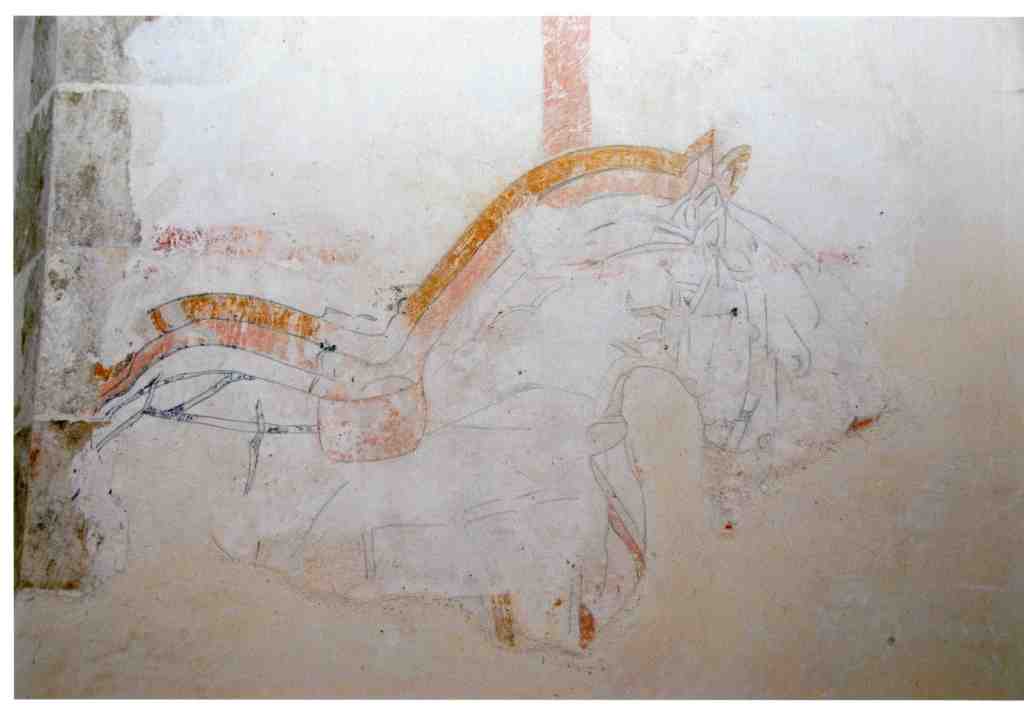

Around 1400, a furtive hand incised graffiti in the plaster in the tower. The figure, hunting with two hounds, wears a fancy chaperone hat with a liripipe dangling forward. His shoes are pointy, of the kind that bishops railed against for the long toes indicated licentiousness, and inhibited kneeling in church. Perhaps it is a portrait of William Rous who lost his Imber inheritance through problems with women and money. Of him contemporaries said he was ‘alwey occupied in lechery and avowtry and took no heed to sew’.1 One can only guess at the opinion of the person who scratched the image above the stair.

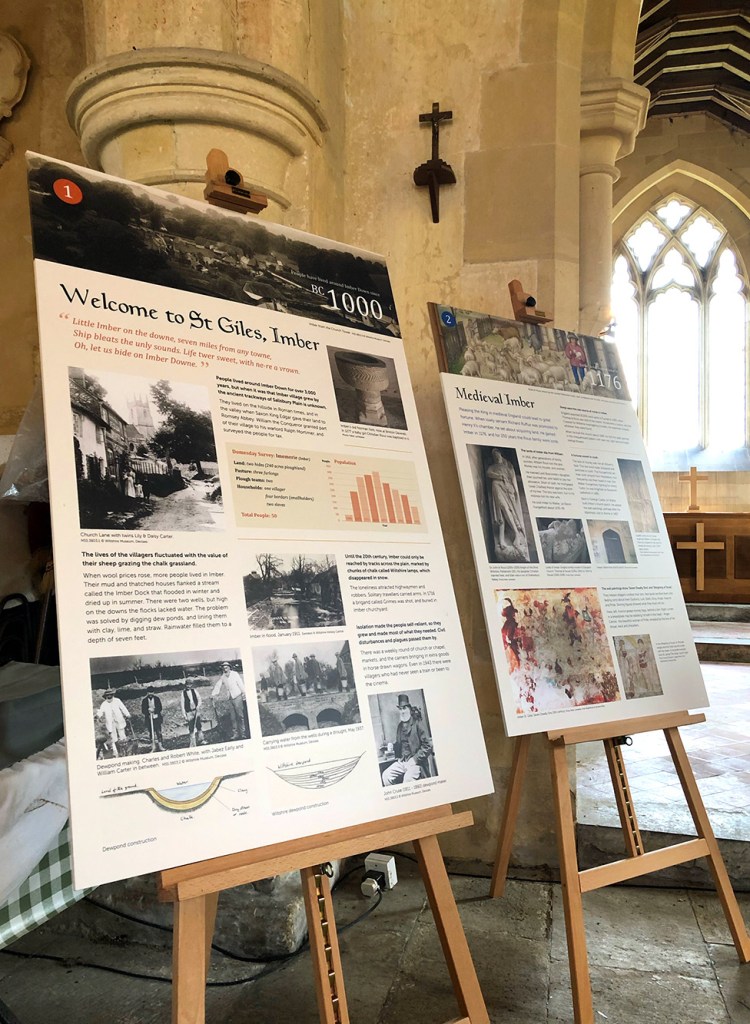

On the day I visited, the church was under wraps, awaiting the next seasonal open day – pandemic allowing. The public visit en masse, so the new interpretation had to be visible to a throng, yet well-spaced, back against the walls, and suitable for packing away during the many empty months.

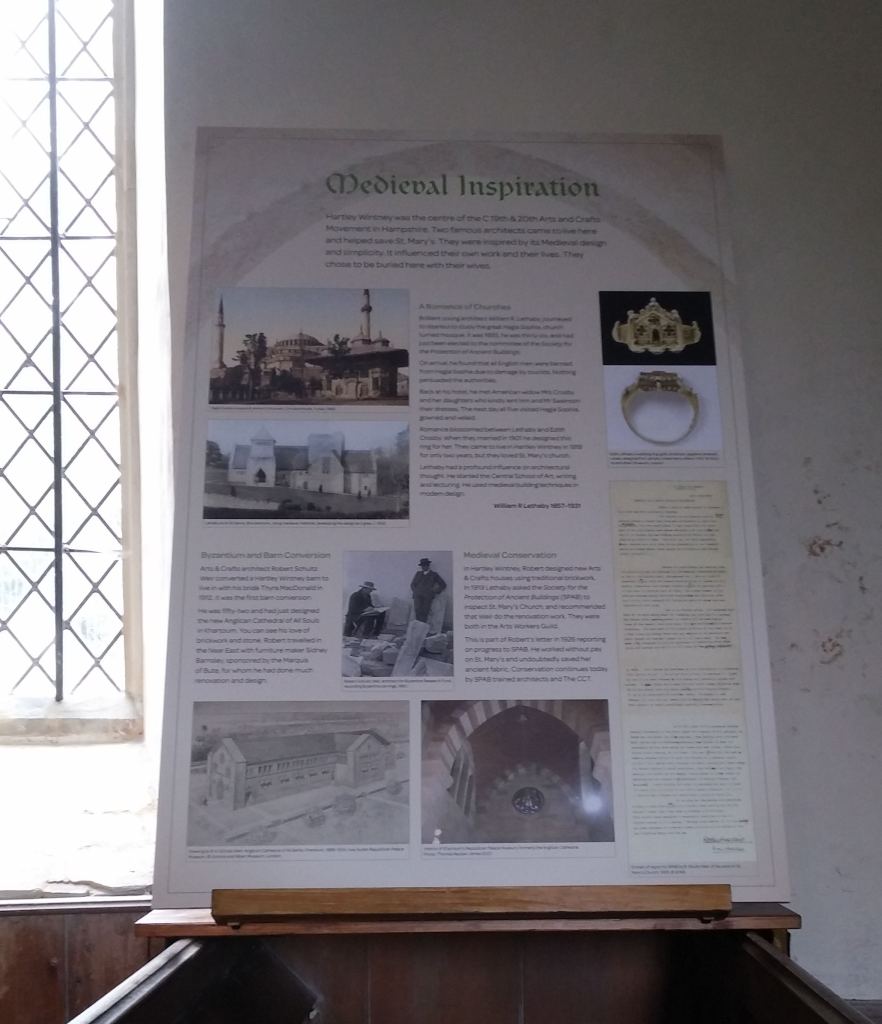

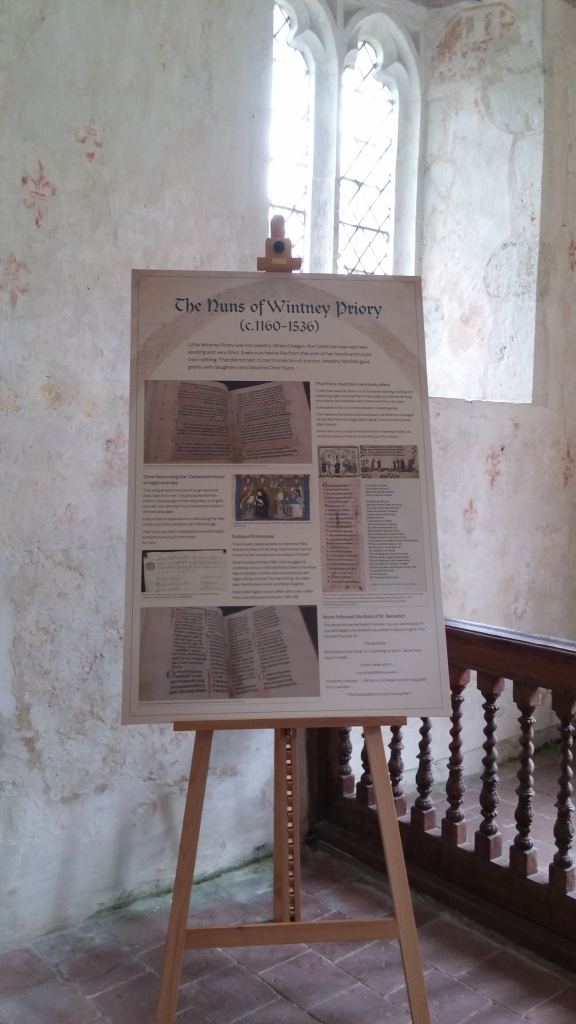

Designers Motivation81 and I had previously collaborated on an exhibition for Hartley Wintney St. Mary’s Church, the size of a shoe box with rare medieval wall paintings. We devised a system of portable lecterns over the box pews, and free standing easels, so the boards would not touch the ancient plaster. You can read more about the medieval wall paintings in both churches.

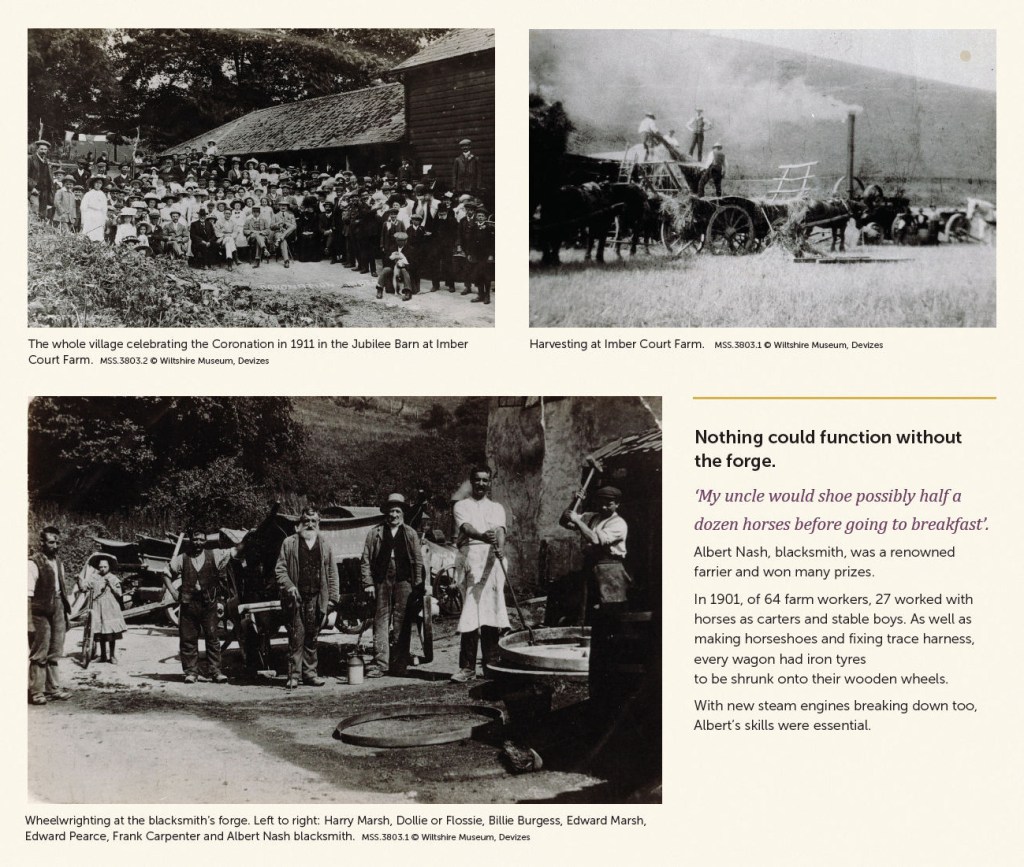

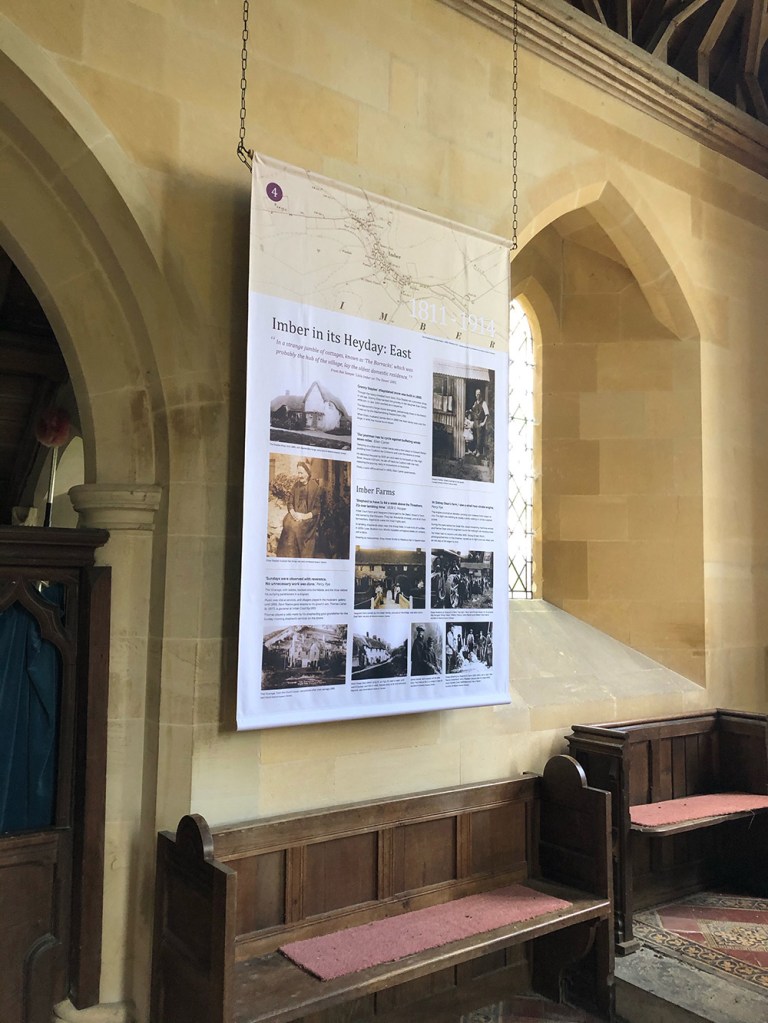

At Imber, we continued the use of easels but chose large banners for the chancel. The photos and information were organised around the 1901 map of Imber, and the censuses of 1851-1911, to find out how the functions of the village interacted and who lived where.

The final banner echoes the Domesday name for Imber – Wild Imemerie, to describe its ancient past and wild present. Richard Osgood, Senior Archaeologist MOD, wrote an expert account of the British Romano villages.

In their contribution, the Salisbury Plain Training Area Conservation Group made this astounding point – the wild turf and flowers from before 1943 still flourish at Imber; and because it lies within the military training area, the 40,000 ha of the Salisbury Plain Training Area is the largest tract of unimproved chalk grassland in NW Europe. Protected from intensive agriculture and new building, it supports a wonderfully rich diversity of species. The conservation team supplied fantastic photographs and text to tell of the wildlife of the Plain now.

Neither suburbs nor pesticides smother the lands of Imber.

Left: Stone Curlew. Right: Sainfoin flower with Sainfoin bee unique to Salisbury Plain.

If you would like to visit Imber, see current open days and events

- VCH Wiltshire, Vol 7, 61, note 46.

Confusion arose as Captain Garibaldi changed his mind and handed the ship’s papers to the official agents Cummins of Queenstown. They arranged for its auction at Duneen on Monday 14th. Henry purchased the coals. The ship was bought by the surveyor who had been contracted to value her; but he reconsidered on the way home, and Henry got her at a knockdown price.

Confusion arose as Captain Garibaldi changed his mind and handed the ship’s papers to the official agents Cummins of Queenstown. They arranged for its auction at Duneen on Monday 14th. Henry purchased the coals. The ship was bought by the surveyor who had been contracted to value her; but he reconsidered on the way home, and Henry got her at a knockdown price.

During many hours of painting in the studio, I used to listen to music until at one point the music took over, demanding that I draw the sounds. The images are not intended to communicate the experience of listening to the music, nor to provide a musical text, but they arise from it.

During many hours of painting in the studio, I used to listen to music until at one point the music took over, demanding that I draw the sounds. The images are not intended to communicate the experience of listening to the music, nor to provide a musical text, but they arise from it.